9 January 2018 (updated: 24 July 2020)

Everybody is a designer — uniting your team in empathy for the users

Chapters

Why you need a product development process in which empathy for the users is the binding material of the whole team.

In modern product development, waterfall methodologies seem ancient. Everybody has already gone agile or is in the midst of the transition. Teams work more and more collaboratively, but it is still rare for team members other than designers to actually be user-centered and care about the impact of the end product on lives of real people.

Great products are built on empathy

We all know functional and reliable digital products are not enough to win the customer over. We need to go further and design intuitive interfaces that satisfy the user’s functional and emotional needs.

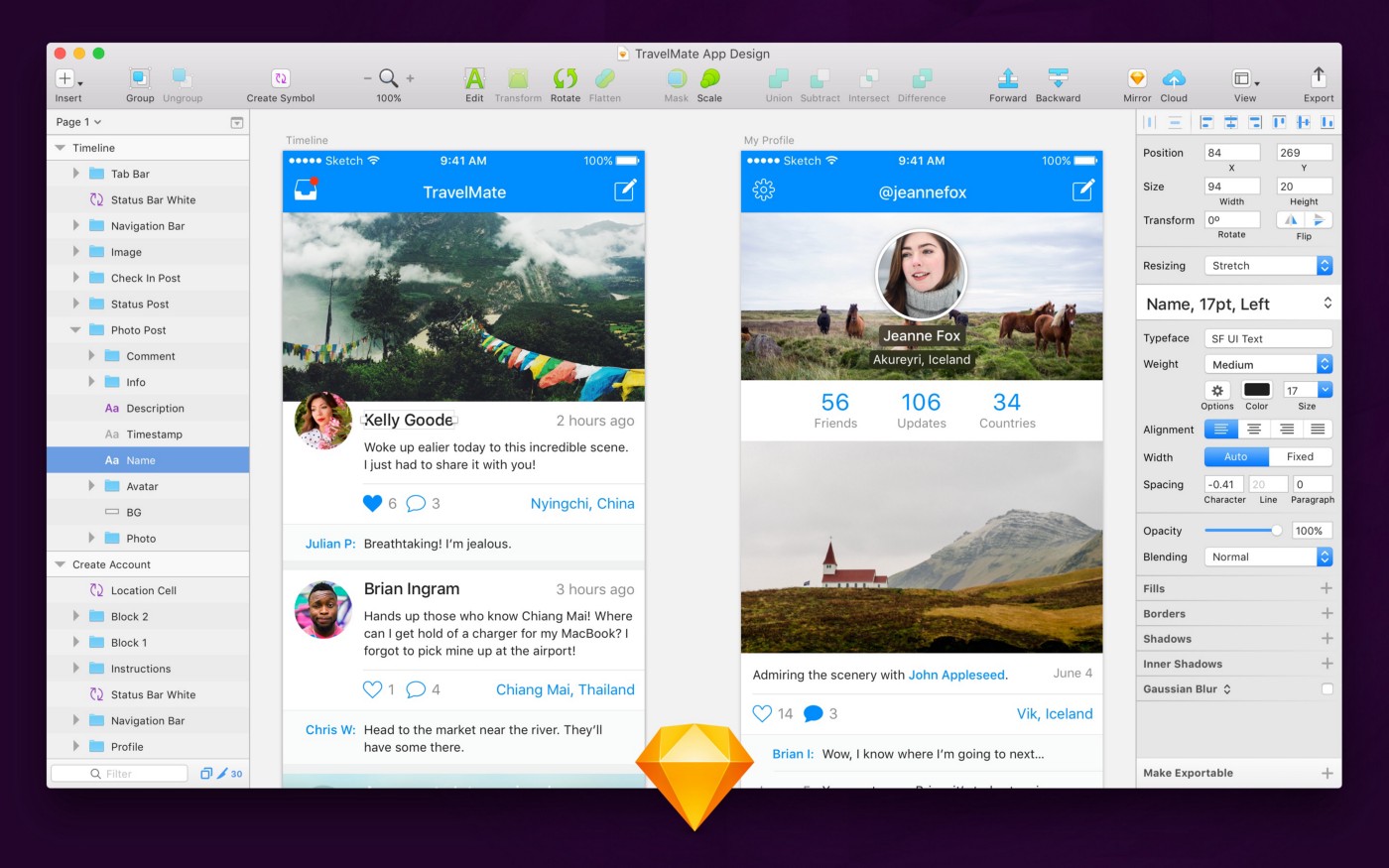

Airbnb, Google, Apple — they all produce great digital design and they all take their users very seriously. However, this approach is not reserved only for big corporate budgets. We are seeing more and more successful products developed by bootstrapped teams who started out with empathy for the users rather than big visions. For example SketchApp, built by a small, passionate team who wanted to challenge Adobe and their bloated software suite, unusable for the average user. Or HotJar, a simple analytics tool which provides designers and marketers with the easiest way to extract relevant information about their users’ behaviour.

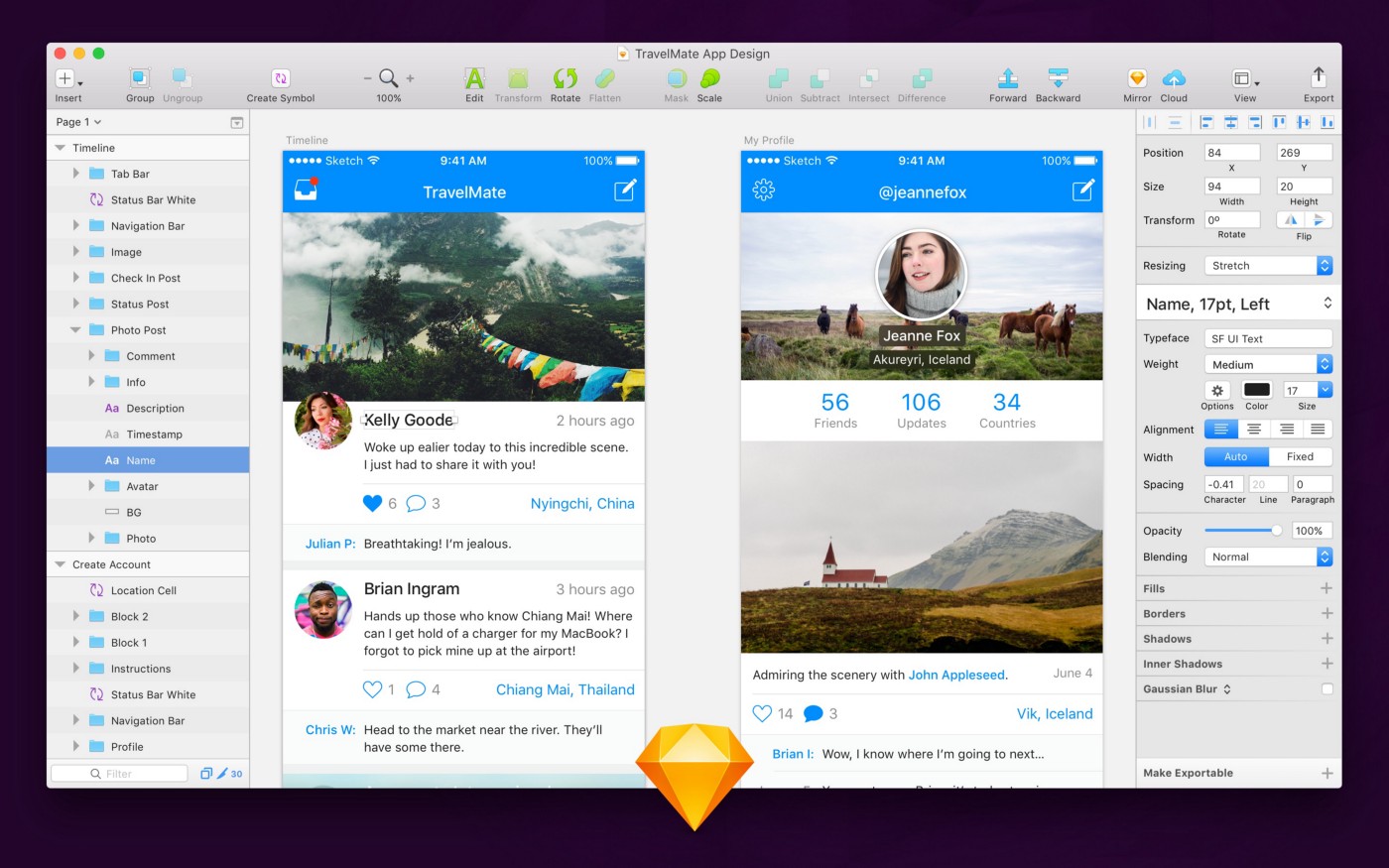

SketchApp has been built from scratch specifically for UI designers | source: sketchapp.com

SketchApp has been built from scratch specifically for UI designers | source: sketchapp.com

Everybody has impact on user experience

Do you think that because you’re a back-end developer you’re not designing? Any, even the smallest or indirect, input you have into the end experience makes you a designer of some sort.

Have you ever informed the team about an observation or a thought you had about the product’s concept? You’re a designer.

Have you ever sketched out an idea? You’re a designer.

Have you ever helped prioritise the product backlog? You’re a designer.

Are you an engineer developing the latest winter car tyres? You design the user’s experience.

Et cetera, et cetera.

There has been plenty of articles listing that kind of examples. E.g. Jared Spool’s “The Power of Experience Mapping”, where he mentions Netflix’s performance engineers and their impact on load times, which makes them experience designers.

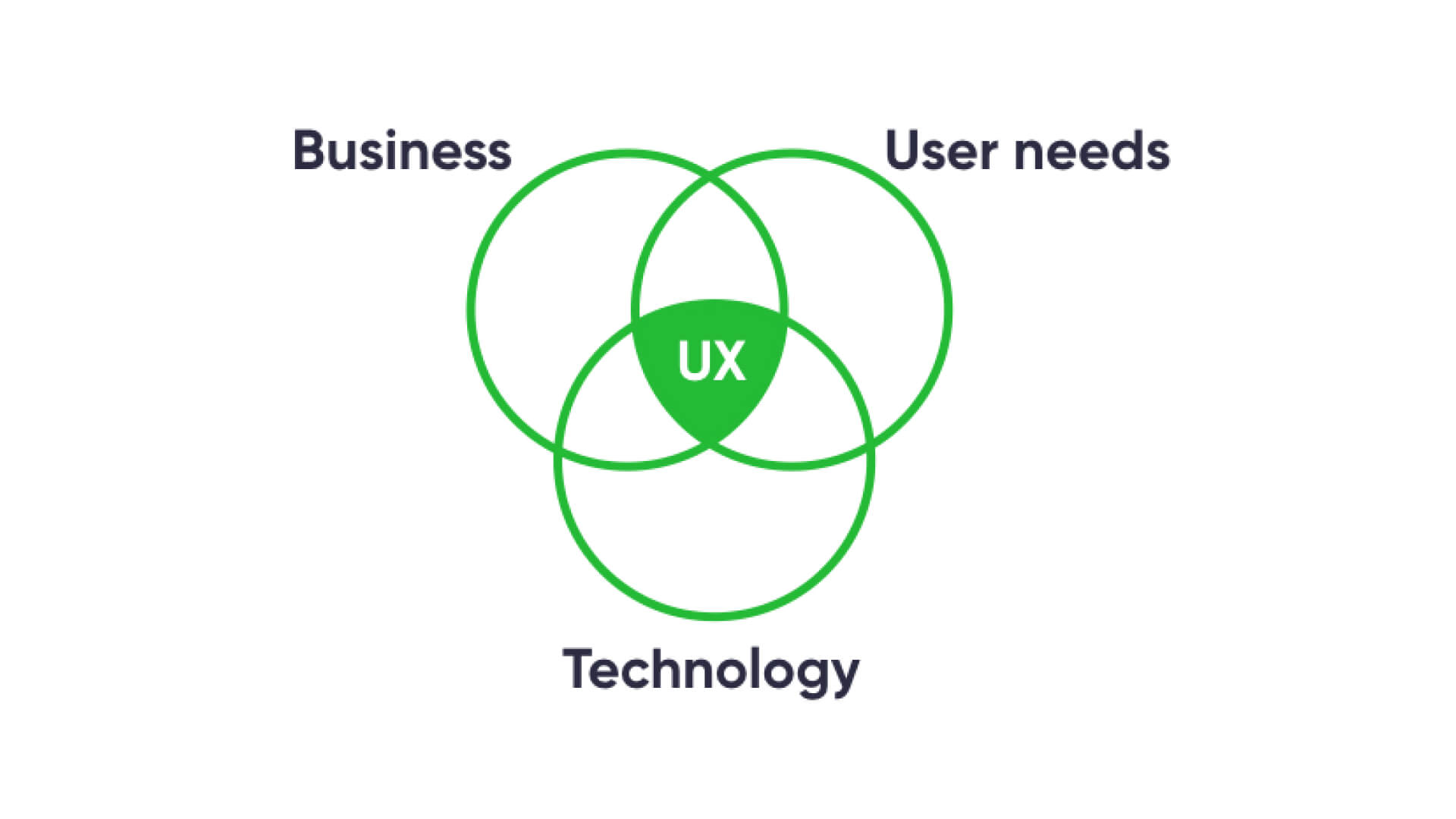

It is sort of obvious to modern companies, but I cannot stress it enough — user experience is created at the intersection of business, technology and user needs. When business and technology impact the design, they are a part of the design process. Of course, it doesn’t mean that EVERY SINGLE ONE OF YOU is responsible for the outcome.

In the end, it’s the designer who is responsible for facilitating everybody’s inputs and directing the product’s design in the right direction. It is the designer’s responsibility to share the knowledge about the users with the whole team and build their sensitivity about the real-life use of the product.

The hidden cost of handovers

I know it’s a buzzword, but how to build empathy? Well, only by soaking up our users’ problems and motivations during the discovery phase, and not through personas or customer journey maps. Developers or other non-design specialists hardly ever read them. It typically leads to a disconnected product development process where everybody expects certain deliverables and does their work in silos, not thinking about the impact they have on the end user.

The cost of this is tremendous — time wasted on handovers, pushing out tickets instead of solving problems and disparity of objectives — while designers are focused on the users, developers might strive to address business problems. Too much focus on business goals is risky, because it puts all the weight on the stakeholders’ shoulders. At the end of the day though product will be used by regular people, not your stakeholders, developers or even the designers.

What I observed in the industry and what I am guilty of myself is the tendency for design teams to create a monopoly around customer insight and the design process. Designers sometimes think their designs are their own beautiful babies whom they do not want to share with others. However, the more you share, the richer feedback you will receive and the better design you will create.

Uniting the team in a good cause

I believe that it’s my duty to improve the world a tiny bit by reducing the amount of time wasted and stress created by badly designed interfaces. It’s a good, noble cause, isn’t it?

It feels really good to see your design solve an actual problem for your users. I like to share that feeling with the team, because, in the end, everybody worked together to create that user experience. But how to make people care? How to make the team align in this noble cause?

Well, you need an inclusive design process. Or, in general, a product development process in which empathy for the users is the binding material of the team. Here are some considerations on how to make it happen in your project team:

Include the whole team in the research phase

User research, just like design, shouldn’t be a siloed responsibility of the design team. It doesn’t mean that back-end developers should start conducting ethnographic research, though. But you may start involving non-designers in user interviews or strategy workshops. As I mentioned before, it’s about soaking up the user’s world.

Design together

The design phase of many projects will start with workshops where you rapidly generate lots of sketches to explore possible solutions. Such a design studio workshop usually starts with a presentation of the outcomes from user research. It’s a great way to show the whole team that every design decision comes from user needs and is not pulled out of thin air.

Regular design critique sessions

Design critique can be done in a more organised way, e.g. a 2-hour meeting every Friday, during which the whole team can raise their concerns about the designs in a constructive way. Critique shouldn’t be reserved for other designers — great feedback can come from anybody.

Share user testing recordings or involve others

User testing (or usability testing) sessions can be often streamed live for anybody to take a peek. If this is not possible, at least make sure that the whole team observes real users engaging with the interface on a regular basis.

I have followed this approach in a number of projects and companies I worked for. Stakeholders from all backgrounds eventually give in to the power of user-centricity when they see the value which comes from it. One colleague, a senior marketing manager once told me:

Being involved in interviews and this user-centered process was really eye-opening for me. I realised that in marketing, we have been doing everything the wrong way around — all strategy should come from the users, not from us pushing our pet projects.

It’s very powerful to be able to celebrate success or solve problems together. There is no better bond than the one created out in the field, even if the field is virtual. Iterating every week and streamlining the user’s journey bit by bit, button after button, is quite a battle to win.